Seasons of an Argentine ant's life

Argentine ants in San Francisco live in vast colonies made up of constantly-changing networks of nests. They are uniquely adapted for life in cities, and their population undergoes an annual transformation that scientists have yet to understand.

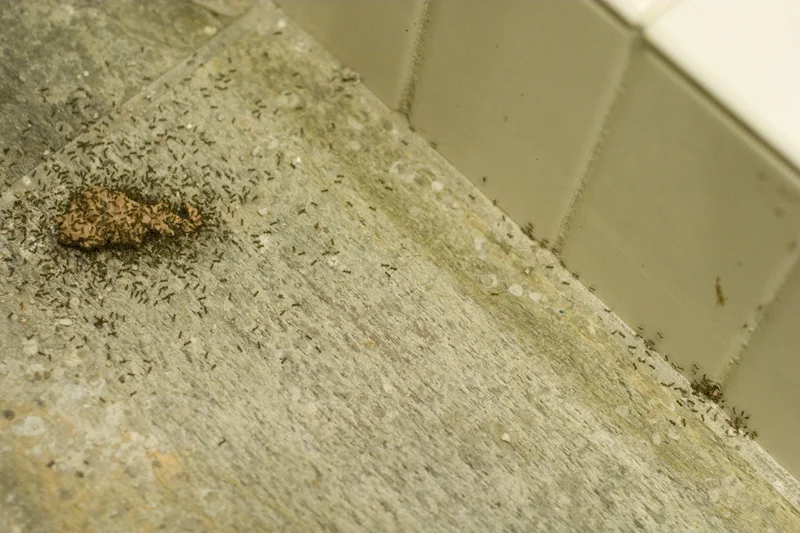

Ants invade the offices of What's That Bug?

City Life

L. humile rely on built structures for shelter and water. "In San Francisco, we have two peak periods when they come inside," Stanford biologist Deborah Gordon explained. "In winter, when it rains, they come in on the pipes because it's warm and dry inside. But the peak time is in September and October when it's hot and dry outside. They find their way inside by tracking humidity condensing off the pipes. If they come into [your house] and find someplace that's hospitable, a queen and some workers will move in." Contrary to popular assumptions, the ants aren't coming inside to get your food. Mostly they want water, and "food seems to be only an extra bonus," Gordon said.

So if you're wondering why your house is invaded like clockwork every winter and summer, the answer is that this is actually part of Argentine ants' natural lifecycle. They live in the exact same habitat that you do. From the ants' perspective, you're trying to displace them from a house that is rightfully theirs—and they would drive you out if they could. That's the same strategy they've used with most of the native ants in San Francisco.

The annual sacrifice

For Argentine ants, spring is the time for their annual sacrifice. Hidden from human eyes, in shallow tunnels beneath tree trunks and underground, the worker ants kill 90 percent of their queens. By one estimate, the queens go from 30 percent of the population to less than five percent. It's hard to say why the workers would do this at the beginning of their mating season; environmental scientist Neil Tsutsui called it "mysterious and bizarre behavior." So far, scientists have not been able to figure out whether this annual sacrifice changes the genetic makeup of the colony. It seems that the queens are killed with little regard for age, fitness, or genetic relatedness to the rest of their sisters.

After the queens have been executed, mating season begins.

An Argentine queen and worker ant. Photo by Alex Wild.

communication

Like most ants, L. humile conveys information to its peers though chemicals called pheromones. They can mix dozens chemical combinations from organs all over their bodies, releasing them into the air as volatiles or leaving them in tracks on the ground. Possibly the best understood of these communication signals is a simple trail pheromone, a mix of two chemicals that an Argentine ant lays on the ground to tell her sisters "follow this!"

At Tsutsui's lab in Berkeley, researchers are trying to crack the code on ant pheromones. They've gotten far enough that you might say they can communicate in Argentine ant language just a little bit. To do it, the team used a gas chromatograph and mass spectrometer for chemical analysis, plus low-tech paper and wires for manipulating the ants. First researchers painstakingly analyzed chemicals left behind by ants who walked across wires to reach food. Their goal was to decode the ants' trail pheromone, which turned out to be a combination of two chemicals that attract other ants. Next, Tsutsui's team synthesized their own version of the chemical to see whether it would attract ants. It did. Adding another ant pheromone to the mix made the trail even more attractive, so Tsutsui believes they've found two chemicals that act as ant attractants. Next, the team figured out how to change the chemicals on an Argentine ant's skin so her sisters no longer recognize her as a nestmate. At that point, the ants attack each other. After these experiments, humans now know two phrases in Argentine ant pheromone language: "Follow this trail!" and "Attack!"

In this video, you can see Argentine ant trails, with added color to highlight where the trails are.